|

Post a reply || Back to Message BoardNFA Message Board Balmville School - Historically Significant ?

Message: Saving the Old Balmville School Ashley Fuller Senior Capstone. Fall 2018

Acknowledgements I want to acknowledge Michael Hernandez, Rick Milton and Linda Lou Sully for allowing me to include our emails and their names in my project.

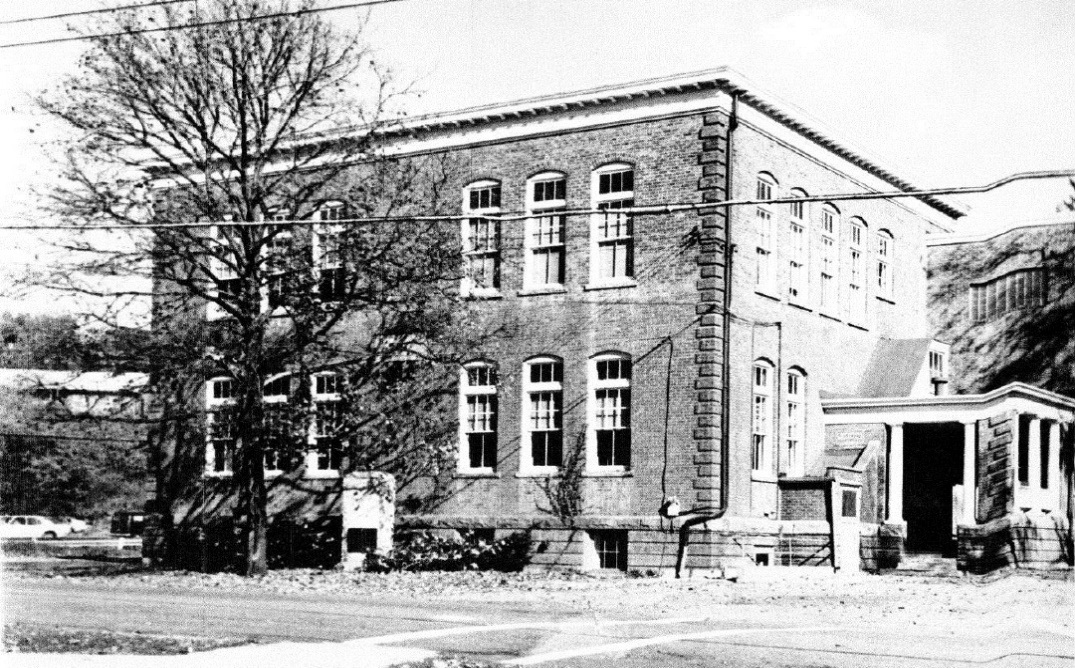

Part 1: What Makes it Historically Significant? Preface Named after the more than three-hundred-year-old Cottonwood tree residents believed was a Balm-of-Gilead, Balmville is a neighborhood within the Town of Newburgh in Orange County, New York. It is situated just north of the City of Newburgh. Newburgh is one of the oldest towns in New York. In 1763, the Precinct of Newburgh was created and in 1788, it became a town. Twelve years later, in 1800, the Village of Newburgh was incorporated out of the Town of Newburgh. In 1865, the Village became the City of Newburgh. Although the Town and City are separate municipalities, much of their history is intertwined and they have affected one another. For this project, their histories will be written as one. When referring to one specifically, the text will state “Town of,” “City of,” etc. Chapter 1 Introduction Newburgh is one of the oldest towns in New York. It was once known as the grandest city in New York, withits beautiful architectural houses designed by Andrew Jackson Downing and Calvert Vaux, the shops on Water and Front Street, and the breath-taking views of the Hudson from Newburgh Bay. However, in the 1960s, Newburgh began to decline. Its once rich history has been lost under the crime and decrepit eighteenth and nineteenth century buildings. Newburgh’s past has been slipping through the cracks. Urban Renewal destroyed much of Newburgh, yet much still remains. These buildings are being left to decay until they cannot hold their own weight anymore. The purpose of this project is to examine the historical significance of the Old Balmville School in Newburgh’s neighborhood of Balmville. Through this research I have found the Old Balmville School and its location to be associated with people and periods of significance making it eligible for the State and National Registers of Historic Places. Chapter 2 Palatine Settlers The land upon which Balmville lays was part of the original land purchased by Governor Thomas Dongan from local natives in 1684. It stretched from New Paltz to Haverstraw—roughly fifty to sixty miles. In 1694, Captain John Evans was granted a large patent of the tract—nearly fifty miles. When the English government discovered this, they annulled the patent in 1699, and granted eighty-two small tracts. The area known as “Quassaick Creek and Thanskamir” included much of Newburgh and the surrounding areas known today. Those first to settle in the area were refugees fleeing the destruction of the French on the Rhine. Led by Reverend Joshua Kockerthal, the party of forty-one Germans looked to the Queen for help. In February 1708, they asked for passage to England. When they arrived in London, Kockerthal petitioned the Queen to send them to the English West Indies. Realizing the party’s desperate need of aid, the Board of Trade, on behalf of Kockerthal, asked the Queen to consider his petition. A May 10, 1708, Act of the Privy Council, stated: “We humbly propose, that they be sent to settle upon Hudson’s River in the province of New York; where they may be Usefull [sic] to this Kingdom, particularly in the production of Naval Stores, and as a frontier against the French and their Indians.” They set sail in mid-October 1708, their journey taking nearly nine weeks. When they arrived at Flushing, Long Island, it was the dead of winter and conditions were too harsh to travel north, so they stayed in New York until winter’s end. The exact date in which the party reached the “Quassaick Creek and Thanskamir” area is unknown but assumed to be early 1709. Original plans stated their settlement would be a frontier and producers of naval stores, but neither occurred. (Knittle, 41) It would be ten years before the Germans were granted any land. The area was made up of ten tracts from the eighty-two patents created in 1699. The first of these was known as the German Patent containing 2,190 acres issued December 18, 1719. The patent included the present City of Newburgh and parts of the Town of Newburgh and Balmville. The patent was then split into ten lots, one of which was five hundred acres granted to Kockerthal for a Glebe and forty acres left for roadways. Lots six through nine were what is now the majority of Balmville. North of lot nine was four hundred-and-eight acres that “remained unconveyed by patent until after the Revolution.” These acres, also included the other half of Balmville including the namesake tree. Author David Barclay believed this acreage was intended to be part of the German Patent. On June 19, 1786, Surveyor General of New York issued a land certificate stating Samuel Edwards, James Demott, Isaac Demott, John Roe, William Bloomer and Eleazer Lucey were entitled to lots with the acreage for their military service during the Revolutionary War. On November 17, 1786, each was granted a patent. Bloomer property consisted of the majority of the four hundred-and-eight acres. Chapter 3 Washington’s Headquarters America had already been at war with Great Britain for seven years when George Washington established his headquarters in the Precinct of Newburgh. In April 1782, Washington, along with his Army, made his way into Newburgh choosing to make his headquarters at the late Colonel Jonathan Hasbrouck’s farmhouse. Prior to Hasbrouck’s death in 1780, he had served in the Ulster County Militia where he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1774. The following year, at the start of the war, the Committee of Safety and Observation was created which he was a member. Some of their meeting were held at Hasbrouck’s home. While in Newburgh, Washington made critical decisions that had a hand in shaping the future of America. Discontent grew amongst the Army as they had not been paid for their military service. This dissatisfaction lead to distrust in a Republic. Colonel Nicola was tasked with discussing the possibilities with Washington. On May 22, 1782, he sent Washington a letter expressing his concerns that a Republican government contained too much weakness. Adopting a government that “led us through difficulties’” would also lead them to “‘the smoother paths of peace.’” Nicola proposed a title “‘more moderate’” for Washington. He believed “’strong arguments’” for the title of “King” could be made and it would come with “‘material advantages.’” Washington’s response stated Nicola’s letter left him with “‘great surprise and astonishment… no occurrence in the course of the war has given me more painful sensations, than your information of there being such ideas.’” Washington’s abhorrence and refusal of a monarchy gave America its democracy. Still, tensions grew as the lack of payment continued. Known as the Newburgh Conspiracy, in March 1783, anonymous letters began to circulate around the Army calling for a mutiny against the Continental Congress. On March 15, Washington ordered an emergency meeting to address the Army. He spoke of his own “constant champion[ship]” having never left their sides. He was “witness [to their] distresses” and stepped forward on their behalf. He was grateful of their presence giving “me a sence [sic] of … confidence. The sincere affection I feel for an Army, I have so long had the honor to Command, will Oblige me to declare… in the attainment of compleat [sic] justice for all your toils & dangers.” And with his pledge—the Newburgh Address—Washington prevented a potentially devastating upset for the future of America. On April 18, 1783, exactly eight years to the start of the war, at his Newburgh Headquarters, Washington announced the Proclamation for the Cessation of Hostilities ending the war. On April 10, 1850, an act of legislature put the house into the hands of the Board of Trustees to preserve. It became the first publicly owned and operated historic location in the country. It was also the first Historical Landmark and is included in Newburgh’s East End Historic District. Chapter 4 Industrial Hub Newburgh was already a growing industrial hub before the nineteenth century. Its location on the Hudson River and proximity to New York made it the ideal transportation center. With the advent of shipping goods via waterways and railroads, Newburgh’s waterfront became its business center. Railroads littered the shore and docks stretched for two miles. Combined, these two modes of transportation were “the key to commerce” and were responsible for Newburgh’s prosperity. The increase of transportation brought jobs. It did not take long for Newburgh to become wealthy. Transportation Prior to the Revolutionary War, colonists were forbidden by the Crown from manufacturing and had imposed importing only laws. In 1730, Cadwallader Colden built the first dock on the waterfront. Some began to sail their sloops out of Newburgh to the West Indies even before the war. The war’s end witnessed trading on the river begin to increase. By 1798, there were four sloops lines out of Newburgh. Sloops were used until 1828, when the Benjamin Carpenter Company built the steamboat William Young to transport freight and passengers from Newburgh to New York becoming one of the first to do so on the Hudson River. The Newburgh and Fishkill Ferry was established in 1743. Sailboats and rowboats were originally used until 1816, when a horse-boat was built. In 1828, steamboats began to be used. Thomas Powell purchased the ferry from John Peter Dewindt in 1835. He remained the proprietor until he gifted it to his daughter in 1850. The Erie Canal was opened in 1825, stretching from Buffalo to Albany. It would prove to be beneficial; however, Southern New York would not see any of it. The answer was found in railroads, still early in its infancy. The New York and Erie Railroad was charter in 1832, with plans to connect the Hudson River, at Piermont, to Lake Eire, at Dunkirk. Already feeling the pressure from the opening of the Delaware and Hudson Canal—from Pennsylvania’s coal fields to the docks at Rondout near Kingston—in 1829, Newburgh knew the opening of the railroad would significantly cripple their shipping efforts. New York State granted Newburgh a charter in 1835, for the construction of the Hudson and Delaware Railroad meant to travel from Newburgh to the Delaware River in order to reach the coal fields. In turn, Newburgh would become a terminus of the New York and Erie Railroad. The charter was abandoned when disagreements arose between Newburgh and Goshen. Ten years later, Newburgh would try again. This time they succeeded. By 1840, Erie was in financial strain. Newburgh offered to pay them in exchange was a railroad to Newburgh. Understanding the effect not having the Newburgh Branch would have on the Village, Homer Ramsdell continued to put money forth. He was elected the local director of the New York and Erie Railroad and eventually because the president. The Newburgh Branch officially opened on January 9, 1850. In 1869, a second branch was opened. The Pennsylvania Coal Company opened a dock in Newburgh in 1867, becoming one its largest commodities. Newburgh now had a direct link to the coal fields and iron deposits in Pennsylvania. Being amongst the cheapest in coal trading, they became the “principal gateway” for coal shipments to New England. In 1881, the New York and New England Railroad was opened. Railcars were ferried across the river to Fishkill Landing. Its life was short-lived. In 1889, the Central New England Railroad opened. It was a railroad bridge over the Hudson from Highland to Poughkeepsie. Many more railroads would eventually be constructed and connect to Newburgh helping the city expand. Manufacturing and Commerce The opening of the Newburgh Branch caused an influx of industries, manufacturers and businesses to relocate to or open in Newburgh. An abundant of factories and storefronts cluttered Newburgh; from the Rose and Jova Brickyards north of the city to Whitehill and Cleveland’s “Never Rip” branded clothing. Each had a hand in Newburgh’s rise and helped it prosper for a century. After George Washington’s departure, farms began to develop, and Newburgh saw its economy rise. Grain became a popular commodity. Mills were established near creeks in order to use their water power. Grist mills like the Gidneytown Grist Mill—built in the early 1800s—were established. They were found useful to farmers that wanted to process their grains. Newburgh’s freighting business truly began with the rise in local farming. Sloops and schooners transported goods to the New York market. As the New York population grew so did their need for milk and butter. Farmers made the transition to dairy farming becoming New York’s largest supplier. The roads leading to and from Newburgh were in horrible condition hindering farmers attempting to travel to the waterfront. In 1801, a group of freighters, including Thomas Powell, built a turnpike from Newburgh to Cochecton, roughly sixty miles. This enabled farmers from a larger area to travel to Newburgh. Freighters and the city benefited from this as it produced more means. In 1841, the Orange County Agricultural Society was established. With members from all over Orange County, it was “organized to promote agriculture, horticulture, the mechanic and household arts.” They established the annual agriculture fair where exhibits showcased local produce and farming equipment such as the Chadborn and Caldwell Manufacturing Company’s “Excelsior Roller Mower”—the first American produced lawnmower. A note worthy mill is the Gomez Mill House. In 1714, a Jewish leader, Luis Moses Gomez, bought a thousand acres in Northern Newburgh. Eventually, he came to own over four thousand acres. He established a “firestone blockhouse to conduct trade and maintain provisions.” Wolfert Ecker, an American patriot, came to own it next. He built additions to the house including secrets passageways as he used it as a meeting house for the Revolutionaries. The house would next fall into the hands of William Henry Armstrong, a nineteenth-century conservationist that added to Newburgh’s farming wealth. The most famous owner was Dard Hunter, a twentieth-century artisan and paper historian. He built a paper mill on the nearby creek. People would travel from all over to watch Hunter make paper by hand. The house was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. The Gomez Foundation for Mill House was founded to establish a museum and preserve the house. The Gomez Mill House is the oldest Jewish dwellings with nearly three centuries of continuous living, still standing in North America. Its also the only mill left in Newburgh. Chapter 5 Thomas Powell The impact Thomas Powell left on Newburgh and the people was greatly influential. He left a lasting legacy and his name to Newburgh. He was born February 21, 1769. He lived in Hempstead, Long Island with his family. They lived in poverty and struggled to get by. In 1781, Thomas’s father, Henry, drowned attempting to save one of his sons. At twelve, he, and his older Jacob, sixteen, were left to take on the responsibilities and aid their widowed mother. In 1788, they relocated to Washingtonville in Orange County then later to Marlborough, Ulster County, in 1791. The brothers opened a store and built lime kilns where they produced and sold lime. In 1798, in hopes of making it in the mercantile business, they moved to New York, but the onset of yellow fever drove them to Newburgh to wait out the epidemic. When they arrived in Newburgh, all that occupied the village’s commerce was one dock and a few stores. Seeing potential, the brothers quickly joined the mercantile and freighting business. In 1802, Thomas purchased the sloop Favorite and established the Thomas Powell Company. His company built the steamer Highlander, known as the safest boat on the Hudson, in 1834. In 1844, Powell’s son-in-law, Homer Ramsdell, joined his operations establishing Thomas Powell and Company. In his later years, Powell spent time in retirement leaving business matters to Ramsdell, but in 1846, he came out of retirement to build the steamer Thomas Powell, the fastest boat on the river. In 1848, Powell and Ramsdell sold Thomas Powell to captain Absalom Anderson—he later commissioned the build of the Mary Powell, the most well-known steamer of the Hudson Valley. They then built the Newburgh, the first barge to be built in Newburgh. Thomas Powell’s freighting business was significant, but it was not his only venture. In 1806, he was a member of the Firehouse #2. He was a member of the original Agricultural Society of Orange County from its inception in 1818 to its end in 1825. (Eager, 62 & 68) When the Hudson and Delaware Railroad charter had been voided, Powell attempted to have the charter reinstated. In 1836, legislature passed “to renew and amend” the charter. It was now named the Hudson and Delaware Railroad Company and Powell was elected its president. He created the Powell Bank of Newburgh in 1838. Besides all of his own businesses, he also aided others that were in need of getting afoot. Thomas Powell died on May 12, 1856. Known as one of “the fathers of Newburgh”, Powell left a huge impact on Newburgh and its citizens. His death was a “public loss.” He was a humble man who used his wealth to develop Newburgh and gave it its success. He contributed to the buildings of the village creating jobs for hundreds of people. Samuel W. Eager described Powell as “unostentatious, liberal where it is a virtue to be so,” leaving his door open for all those that needed it. Robert Boyd Van Kleek published a memorial the following year. He said it best: “The name THOMAS POWELL is written in living characters on every page of our local history and progress.” Chapter 6 ArchitectureNewburgh is an architectural wonder. The East End Historic District contains over four thousand nineteenth-century buildings in architectural styles such as: Greek Revival, Federal, Italianate, Second Empire, Carpenter Gothic, Queen Anne, High Victorian, Romanesque Revival, Gothic Revival, and Picturesque. The architectural masterpieces that cover the city and town are owed to the renown architects that called Newburgh home at one time or another. Andrew Jackson Downing was born in Newburgh in 1815. He was a horticulturist and landscape architect known as the “Father of American Landscapes.” He wrote articles for the Horticulturist and authored many books. His writings were “the reason for Newburgh’s wealth of architectural wonders.” In 1850, he traveled to Europe where he met English architect Calvert Vaux. They established a partnership and traveled back to Newburgh where they designed estates through the Hudson Valley. Vaux published Villas and Cottages, a book containing the many designs created by Downing and himself in 1857. In 1850, Downing was commissioned to design the grounds of the Capitol, the White House and the Smithsonian Institute. His untimely death in 1852, kept him from finishing. Vaux and Frederick Clarke Withers, a prodigy of Downing’s, carried out his designs. Before his death, Downing and Vaux began developing a design for a great park. In 1856, Vaux moved to New York and connected with Frederick Law Olmsted whom also had been influenced by Downing. Together they worked on a design they called “the Greensward Plan.” In April 1858, they submitted their plan which would become Central Park. Vaux and Olmsted would continue to design many more parks throughout New York. In 1889, they were commissioned by Newburgh to design the Downing Park in honor of Downing. Both would leave a legacy throughout America due to the teachings of Andrew Jackson Downing. Chapter 7 20th Century and the Decline The end of the nineteenth century, the United States experienced the Panic of 1893. This economic depression severally crippled industrial cities. Newburgh was no exception. Steel and iron works were cheaper in the Midwest causing businesses to leave. Some local business went bankrupt, but Newburgh was able to survive and began manufacturing other goods like clothing and pocket books. In the early twentieth century, Newburgh began to prosper again. During World War I ships were built at the docks. Newburgh had become a tourist destination. People traveled from all over to walk the grounds of Washington’s Headquarters, shop in the business district, or stay at the Palatine Hotel. After World War II, Newburgh boomed once again. In 1930, Archie Stewart, a local from a prominent diary farming family, donated land to Newburgh for the use of an airfield. In 1934, West Point began using the Stewart Airfield to train cadets. After the war, it was converted into an Air Force Base. This brought a surge of new people to Newburgh, increasing its population to around 32,000 in 1950—the highest it has ever been. Look magazine named Newburgh an “All-American City” in 1952. And in 1960, Mount Saint Mary’s opened its university on the property that once held Thomas Powell’s homestead. But things began to decline again, and the city was not able to get back up.Industries found themselves, again, relocating to the West or South for cheap labor. In 1969, the Stewart Air Force Base closed sending a large amount of Newburgh’s population away. This left empty housing and the loss of demand which meant there was no need for supply. In 1957, Interstate 87 (New York Thruway) was opened to the West of the city. In 1963, Interstate 84 and the Newburgh-Beacon Bridge was opened north between the town and city. The bridge made the ferry obsolete. Now travelers looking to cross the river had no need to enter the business district. The interstates not only created a bypass, but they made shipping goods farther easier and cheaper. Shopping center and strip malls replaced family-owned businesses. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) made it easier to buy a house rather than rent. People began moving to the suburbs where mass-produced tracts of houses became the desirable place to live. By the early 1960s, Newburgh had become dismal. People began leaving larger cities like New York for Newburgh in hopes of finding cheaper living accommodations. The Great Migration sent people north in search of opportunities. However, Newburgh was already rapidly declining, and these opportunities did not exist. Of the those that began to settle, the majority were African-Americans who were not welcomed. They were left economically and socially displaced. Forced to live in the desolate decay of Newburgh, many received public assistance, as welfare was their only means of staying afloat. Joseph Mitchell, city manager, blamed them, for their “presence encouraged the creation of slums, social blight, and the degradation of social values.” He looked for a way to release the city of the “’chiselers, loafers, and social parasites.’” In 1961, he announced a “’war on welfare.”’ His plan was to prevent any “able-bodied, employable or ‘immoral’” people from receiving aid and limit anyone approved to just three months annually. 1962, the State Supreme Court ruled Mitchell’s plan void, but he had already left his mark. In the 1960s and early 1970s, many Hudson Valley cities experienced Urban Renewal, but Newburgh suffered the greatest loss. In 1959, the Newburgh Urban Renewal Agency approved the Water Street Urban Renewal Program. It included twenty-six acres encompassing Water Street, Smith Street, and Montgomery Street between Second Street and Broad Street. Three hundred twenty-three families were displaced. The $3 million plan was to include a public housing project, an office complex, a shopping plaza, an industrial park and marina. Fifty-five years later, Newburgh is still waiting for the promise of redevelopment. In 1964, another plan was approved; the East End Urban Renewal Project. A much larger project, it encompassed 102 acres, displacing 500 families at $15 million. A local group of preservationists were able to save the district and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. They were also able to save the 1835, Dutch Reformed Church which was added to the National Register in 1970. However, they were not able to save the 1893, Palatine Hotel, once a tourist destination for its glamor. It was razed in 1970, for a county office building that was never built. In total, 1,300 buildings were demolished. Nine streets met their fate with a wrecking ball. The business center that made Newburgh once so prosperous a century before, had vanished. An entire community of businesses and residences were uprooted “causing hardship to thousands.” Urban “Renewal” was a renewed sense of value in the city. More and more citizens began to stand up and protect the historical landmarks of the once rich city. Chapter 8 The Old Balmville School The Newburgh school system was established in 1852, ten years before “common” schools became a reality. Before the Revolution, any education was organized by the settlers in order to instruct their own children. After the war, “there was a great awakening” throughout New York when the necessity of education became apparent. Private schools began sprouting all over the states. In 1784, New York passed the University Law creating the University of New York. However, the state believed in aiding private schools rather than the “common” school leaving those children in poor rural areas out of a proper education. William Bloomer owned a sizable amount of property in Balmville. When he died in 1824, he left half his estate to be split between his sons, John, Jacob and Thomas, and the other half to be split between his daughters, Mary, Abagail, Rachel, and Bethiah. Through a handful of sales, Jacob came to own the property the school would be located on. He died in 1851, and left his son, Andrew, as his executor. A November 3, 1851, court order stated the property once belonging to Jacob’s estate must be sold at auction. On March 3, 1852, Frederick J. Betts was the highest bidder and became the new property owner. {NY Land records] The following month, Betts sold the property to Joseph K. Wiles. [NY Land Records] After Wiles’ death in 1867, his wife, Elizabeth, was left owner of the property. [NY Probate Records] When she passed in 1888, she left a fifth of her estate to the children of her two daughters, Mary and Eliza, a fifth to each of her three grandchildren. [NY Probate Records] After a few sales between those who inherited property, her son, Charles, came to solely own the property in 1889. Charles sold the property to Warren Delano on February 26, 1889. [NY Land Records] The First District School in Balmville began as a one-story brick building about a mile north of the Balmville Tree. In 1896, it could no longer accommodate its growing student population and they were in search of a new school building. In 1896, Warren Delano donated property to the district. On November 24, 1896, for the sum of one dollar, Delano sold the property, currently on the corner northeast corner of Fostertown Road and 9W, to Edward W. Dubois, the trustee for the First District School of Newburgh. Although the deed states a dollar amount, the property was a donation for the purpose of building a school. The property was described as follows: Beginning in the line of the Plattekill Turnpike at a point thirty feet Easterly of John B. Corwin’s lands and running thence easterly along said turnpike road to land of the heirs of Joseph K. Wiles, deceased, thence northerly along said lands to the Northeast corner thereof thence Westerly along the line of Frederick J. Betts land to a post thirty feet easterly of said Corwin’s land thence Southerly in a straight line to the place of beginning. Delano’s daughter, Annie Delano-Hitch, was a long-time friend of the school. She helped fund the school building’s construction in hopes that it “would serve the community for years to come.” A cornerstone on the school indicates construction began in 1897. Originally, a “one and one-half story brick building and clapboard building was erected.” Later, Frederic Hitch, Annie’s husband, donated funds for a second story addition. In 1939, five acres was purchased across Fostertown Road for a playground. The grounds north of the school were used as a garden for students. The second addition was built in 1948, for the Kindergarten class. Two years later, a second-story was added for the sixth-grade students. By 1953, the school had outgrown its location again. Unable to build anymore, their best option was to use the playground. On September 7, 1954, the new Balmville School was opened. Kindergarten through third-grade classes were moved to the new school and the others stayed in the old while using facilities at the new school. Some classes remained held in the old school until the mid-1970s. It was then used for administrative purposes until the 1980s when it was left empty. Chapter 9 Delano Family The Delano family’s footprint in the Newburgh area began in 1846. Warren Delano II was born July 13, 1809, in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. The Delanos were a family of sea traders in New England. In 1833, Warren began his maritime career and sailed to Canton, China where he became an associate of the shipping firm Russell, Strugis and Company. In 1840, he was made partner and expanded the company’s trade to opium. His career made his family among one if the wealthiest. When he returned to the United States in 1843, his wealth made him a “suitable match” for Catherine Robbins Lyman, the daughter of a prominent Massachusetts Supreme Court judge. As his family began to grow, he was called back to China. He decided to send his family to the Newburgh area to stay with his brother. When he returned in 1851, he purchased fifty-two acres on the Hudson River in Balmville where he built his Algonac Estate. Warren Delano was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s grandfather. Delano’s daughter, Sara, married James Roosevelt. The Delanos contributed much of their time, resources and money to Newburgh. Warren Delano was a driving force in the Unitarianism of the Hudson Valley. During the 1930s, John Peter Dewindt held Unitarian Church services in his home in Fishkill Landing. In Newburgh, a Unitarian Church was held in a fairly small building. Delano, who was a member of the Newburgh Church, and Dewindt decided to the two. In 1868, the Church of Our Father was established in Newburgh in which Delano was elected president. Colonel Frederic A Delano, son of Warren, purchased part of the property of the old Orange Mills, a black powder manufacturing complex during the nineteenth century. In 1934, he gifted the land to the Town of Newburgh for a park which today is the Algonquin Park. Annie Delano-Hitch was, perhaps, the most giving of the family. She was well established around Newburgh and New York as a philanthropist. Many articles have been found about her donations. She donated to the Red Cross to aid wounded soldiers during World War I. She donated to the New York Tribute’s Fresh Air Fund and to the establishment of the Woman’s Hotel in New York meant for single, working women. She was the president of the Associated Charities Aid of Newburgh. Established in 1866, the program’s aim was “For the discouragement of mendicancy and indiscriminate alms-giving, and the elevation and improvement of the condition of the poor.” She was also a member of the Child Placing Agency—a chapter within the association. Annie, like Warren, was a member of the Unitarian Association. In 1899, she donated $10,000 to the Church of Our Father—the church her father had a hand in establishing. The donation became known as the Annie Delano-Hitch Fund and for her contribution, she was made a trustee of the Tarrytown School. In 1918, she purchased the old Ramsdell Park known as the “Driving Park” and gifted it to the city in hopes that “it would be a large recreational center for every man, woman and child in Newburgh—regardless of race, color or creed.” The Annie Delano-Hitch Recreation Park today is twenty-six acres with a 2,000-capacity baseball stadium, a softball field, three little league baseball diamonds, four tennis courts, four basketball courts, an aquatic center, two playgrounds, horseshoe pitches, a soccer/football field, the Fast Pitch Softball Hall of Fame, and the multipurpose Activity Center. She was the first woman elected honorary membership in the International Lions Club. After her death, a memorial was held annually in her honor. Part 2: Historic Preservation Chapter 10 Public Outcry In 2007, the Board of Education proposed to demolish the old school stating it was on the verge of collapse. However, a Preliminary Structural Assessment Report conducted in October 2007, states the building was sound. The report coupled with the community support to save the school caused the BOE to hold off on the demolition. Many people believe the BOE is only in search of a new parking lot. Their actions the last seven years leans towards that. They have shelved the demolition only to let the building to continue to deteriorate until it’s too late to turn back and actually does need to be demolished. A Facebook page dedicated to remembering Newburgh is filled with memories. A search for “Balmville” on the page shows many posts about the school. Previous teachers and students, alike, share their stories and feelings about the future of the school. The countless “What a shame” comments and the talk of what they would like to see happen to the old building, leads to a community standing together to save a piece of history. Michael Hernandez was a student during the late 1950s and has been a huge advocate in the school’s future. He’s been in contact with the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, local historians, and has attempted contact with the BOE. His belief is that the school’s connection with FDR makes it a historic landmark that should be saved “so our past has a future.” In 2007, Rick Milton, owner of a local realty company, and a colleague, a local developer, offered the BOE a sum to buy the school with intentions of renovating it and leasing it back at a reasonable price. Another option he gave the school was to sell it back “at a low price after five to ten years.” Milton acknowledges that there were some issues with the plumbing but felt they could “overcome them.” He states the BOE never respond to their offer, so they moved on. Last week I received an email from Ms. Linda Lou Sully. She heard about the project from Michael Hernandez and wanted to tell me her story. She let it be known she did not know much of the history other than the average Newburgh resident. I did not believe much, or any, of what she had sent would yield much help, so I did not read it at first since I was not planning on using it. A few days went by and I remembered the email. I decided to read it. Linda Lou was a student at Balmville School, graduating in 1956, as was her father. Her mother was a secretary for the school for many, many years. As I continued to read the five-paged word document filled with her memories, I found myself completely enthralled. She was not providing me with the historical facts I was looking for, but with her history with the school. She provided a sentimental history; a history the community shares. A community with a history of sentiments, is a community that would fight to save the very thing that history is tied to. A community that is proud of its history. To the Linda Lous, the historical fact that the school is associated with the Delanos is not what makes it significant; its their own history that does. This has opened my eyes to so much more. It has pushed me more towards historic preservation. I do not want to just save historic structures because of their age or their architectural style; I want to preserve them because they are someone’s history. You are preserving a person’s history, not a building’s. I want to include something she wrote: [I] have seen the school’s demise. A strong, sturdy red brick building, now fenced off to anyone, desks visible past a blowing venetian blind in a broken window, paint on wood often gone. I would love to see the classrooms again, feel the wood floors under my feet, climb the long stairs, see the windows I often looked out of, be reminded of so many things that occurred there during my life. Now at seventy-three, she can still recall the details in the school. The way she speaks of it is as though she can still feel it. Chapter 11 National Register for Historic Places According to the National Park Service, in order to successfully list a property on the National Register of Historic Places, one must start at the state level. The New York State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) was established by the New York State Historic Preservation Act of 1980 and is administered by the commissioner of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreations and Historic Preservation. Much like the National Registers, the State Registers “are the official lists of buildings, structures, districts, objects, and sites significant in the history, architecture, archeology, engineering and culture of New York and the nation.” In order to be granted historic landmark status, properties must first meet criteria for evaluation before being eligible. Not only are the qualities of history, architecture, engineering, and culture represented, but they must also meet one of the following: a. “associated with events” of significance, or b. “associated with the lives of persons significant in our past,” or c. “embody the distinctive characteristics” of significant architecture like “work of a master” or “possess high artist values,” or d. contains “information important in prehistory or history.” Properties found eligible are “encourage[ed]” to meet nomination priorities in three categories—Promote Economic Revitalization, Generate Board Public Support, and Contribute to Planning and Education. Sponsors, those looking to nominate a property, should first complete a State and National Registers Program Applicant Form and a Historic Resource Inventory Form, as well as any materials—photographs, maps, written materials—to aid in the process. Once evaluated and felt to meet the criteria, a proposal is assigned a staff member to help further the process. If a nomination is “satisfactory” the New York State Board of Historic Preservation reviews the proposal. If they decide to recommend it, the proposal is sent to the State Historic Preservation Officer for final review. Once officially signed, the nomination is entered into the State Register and sent to the National Register for nomination where the Keeper of the Register reviews it. If approved, it will be added to the National Register of Historic Places. The Old Balmville School meets the criteria for historic landmark status. The building itself, is over a hundred-and-twenty years old. Under Criteria B., it is associated with the lives of the Delanos, the maternal family of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the Nomination Priorities categories, it meets the following: Goals of Nomination Proposals That Promote Economic Revitalization State and Federal investment tax credit programs Owners of non-private historical buildings can receive a twenty percent income tax credit for the costs of rehabilitation. Public and not-for-profit grant projects The goal for the school is to make it into a non-profit community center meant to educate. Heritage tourism and recreation enhancement projects When reopened as a community center it will promote tourism and recreation by visitors. Goals of Nomination Proposals That Generate Broad Public Support Projects sponsored by community organizations There are local historic preservation groups and historical society that are advocates for saving local historical landmarks. Projects benefitting from widespread citizen participation The community has made it known they want the school to be renovated and repurposed. Individuals have contacted local and state authorities in attempt to have the school given historical landmark status. Goals of Nomination Proposals That Contribute to Planning and Education Projects that foster pride in community history The community sees and speaks of the historical value in the school. If added to the State and National Register, the community will be allowed to continue sharing the pride of the local history. Projects that foster awareness of historical properties The school is a historical property. Will educate people about its history and the different types of historical properties. Projects that can be incorporated into local school curricula This project can be school curricula as it will be able to educate people on the history of the location and the prominent people that made the city and town they live in today. Chapter 12 The Future The life of the Old Balmville School after being listed on the State and National Registers for Historic Places, will become a community-driven project. The school will need to be renovated. With the twenty-percent tax credit and support from the community, this is possible. Some members of the community have suggested a “history museum,” others, an “art center.” Many have suggested a “community center.” I propose the “Balmville Art and Community Center.” BAC will be a non-profit, community run, art and community center that promotes local history, art and community. It will achieve this in a number of ways. Classes and workshops will be offered once or twice a week. They will be taught by local community members who want to give back. They can range from painting with watercolor, drawing with charcoal, photography, beads, etc. Classes on a specific local history may be given; for example, the dairy farmers in of west Newburgh. As an art center, all artistic forms may be taught. These classes may be indoors but can take place outside. Balmville sits in a beautiful scenic area looking over the Hudson. Much inspiration can be developed here like Gilford Beal, a painter whose piece On the Hudson at Newburgh was conceived on his family estate located half-a-mile from the Old Balmville School. There is no end in the possibilities that came be achieved here. Walking tours of Balmville depicted the historic lay of the land. Festivals celebrating Balmville, the history, or the art. The school is made of two buildings. The original building is two-stories, each with two rooms. The first floor of the main building is the Art Gallery. It showcases community members’ work. Exhibits are changed bi-weekly, but only room at a time so a piece would have a month of exposure. The second floor contains the art studios/classrooms. The second building is two-stories as well. The first floor is the Photo Gallery showcases members’ work. The second floor is a History Museum with photographs, documents and information about Balmville. The basement is the Photo Lab equipped with a dark room for members to use. I propose this plan for the Old Balmville School and believe this community-driven project will greatly benefit Balmville, Newburgh and its citizens. From prominent people to economic stimulating commerce, Newburgh had it all. In the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century, they flourished in mercantile. They were the largest distributor of diary products in the Hudson Valley. Nineteenth and early twentieth century Newburgh saw a booming manufacturing and industrial era. In 1881, citizens watched as the Orange Woolen Mill installed an Edison generating plant to power light within the factory, become one of Thomas Edison’s first powerplant in America. He also created the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Newburgh—the predecessor to Central Hudson—in 1883, giving Newburgh the second municipal in the country to have street lights. John Nutt described 1891, as “a large, bustling, thriving city, equipped with every modern facility.” Newburgh gave the “comforts of the great cities.” The twentieth century brought Newburgh to the forefront of tourism and entertainment. Sometimes referred to as New York’s sixth borough, Newburgh saw the likes of Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra perform at the Ritz Theatre. Then Newburgh entered the mid twentieth century and the “model city” that had been so grand, was no more. Jobs left, and the opportunities went with them. Government policies significantly changed the demographics of Newburgh creating slums and promoting crime. Much of the history was destroyed by Urban Renewal that was backed by an empty promise of rebuilding. Today, Newburgh is slowly rising out of the fire. More people are getting involved in the restoration and preservation of the history that was sparred the wrecking ball, but not time. Many buildings are inching closer to complete downfall, but others still have time. If action is taken quickly, they can be preserved before it’s too late. The Old Balmville School still stands in relatively good condition. However, in the eleven years since the Board of Education proposed it demolition, it has been left to continue to deteriorate. How much longer does it have before it can no longer be saved? Action needs to be taken quickly. The school and its location are associated with people and periods of significance making it eligible for the State and National Registers of Historic Places. By being listed on the Registers, the Old Balmville School can begin its renovation. And as the new Balmville Art and Center, it will breathe back into the community the education it once did when it opened in 1897.

Bibliography Baldwin, John. History and Guide to Newburgh and Washington’s Headquarters, and a Catalogue of Manuscripts and Relics in Washington’s Headquarters. New York: N. Tibballs and Sons, 1883. Barclay, David. Balmville. From the First Settlement to 1860. Newburgh: Newburgh, 1901. https://archive.org/details/balmvillefromfir01barc/page/n7Brittannica Editors. “Andrew Jackson Downing.” Encyclopedia Brittannica. Updated October 26, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson-DowningBruce, Wallace. The Hudson. London: Blackwood and Sons. 1894. https://archive.org/details/hudson02bruc/page/n5Butler, Shannon. “Extracting the Truth from the trade: The Delanos at Home and in China.” The Hudson River at Home and in China. Vol. 33, No. 1. Autumn 2016. 23-43. http://www.academia.edu/30110288/Extracting_the_Truth_from_the_Trade_The_Delanos_at_home_and_in_ChinaCarnes, Marc C. “The Rise and Fall of a Mercantile Town: family, Land and Capital in Newburgh, New York 1790-1844.” The Hudson Valley Regional Review. Vol. 2, No. 2, September 1985. http://www.hudsonrivervalley.org/review/pdfs/hvrr_2pt2_carnes.pdfCity History. “Later 19th Century.” City of Newburgh, New York. https://www.cityofnewburgh-ny.gov/city-history/pages/later-19th-century------. “Early 20th Century.” City of Newburgh, New York. https://www.cityofnewburgh-ny.gov/city-history/pages/early-20th-century------. “The Post- War Years.” City of Newburgh. https://www.cityofnewburgh-ny.gov/city-history/pages/the-post-war-years------. “Later 20th Century.” City of Newburgh. https://www.cityofnewburgh-ny.gov/city-history/pages/later-20th-centuryCornell, Les. “Town of Newburgh Retrospective.” Town of Newburgh, New York. http://www.townofnewburgh.org/Cit-e-Access/webpage.cfm?TID=40&TPID=4844“Downing Park.” City of Newburgh, New York. https://www.cityofnewburgh-ny.gov/downing-parkEager Esq., Samuel W. An Outline History of Orange County: with an Enumeration of the Names of its Towns, Villages, Rivers, Creeks, Lakes, Ponds, Mountains, Hills and Other Known Localities and Their Etymologies or Historical Reasons Therefor; Together with Local Traditions and Short Biographical Sketches of Early Settlers, etc. Newburgh: S.T. Callahan. 1846. https://archive.org/details/outlinehistoryof00eage/page/n5Grant, W.L., James Munro, Sir Almeric W. Fitzroy eds. Acts of the Privy Council of England. Colonial. Vol. 2. London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1910. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x004782155;view=1up;seq=1;size=175Hattem, Michael. “Newburgh Conspiracy.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/newburgh-conspiracy/Headley, Russel. The History of Orange County, New York. Middletown: Van Deusen and Elms, 1908. https://archive.org/details/historyoforangec00headKnittle, Walter Allen. Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration: a British Government Redemptioner Project to manufacture Naval Stores. Philadelphia: Dorrance and Company, 1937. https://archive.org/details/earlyeighteenthc00knit/page/n5“Jewish American Historical Places: The Gomez House.” Jewish Virtual Library. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-gomez-houseMcCue, Robert. Erie Railroad’s Newburgh Branch. South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2014. https://books.google.com/books/about/Erie_Railroad_s_Newburgh_Branch.html?id=_hS9AwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q&f=falseMittelstadt, Jennifer. From Welfare to Workforce: The Unintended consequences of Liberal reform, 1945- 1965. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. 2005. National Register of Historic Places. “How to List a Property.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/how-to-list-a-property.htmNewburgh City Parks. “Architecture.” City of Newburgh, New York. https://www.cityofnewburgh-ny.gov/explore-newburgh/pages/architectureNutt, John J. Newburgh: Her Institutions, Industries and Leading Citizens, Historical, Descriptive and Biographical. Newburgh: Ritchie and Hull, 1891. https://archive.org/details/newburghherinsti01nutt“Olmsted-Designed New York City Parks.” NYC Parks. https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/olmsted-parks“On the Hudson at Newburgh.” The Phillips Collection. https://www.phillipscollection.org/collection/browse-the-collection?id=1998.004.0001&page=9“Our History.” Rock Tavern Unitarian Universalists. http://uucrt.org/about-unitarian-universalism/history/Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. “National Register.” New York State. https://parks.ny.gov/shpo/national-register/------. “Washington’s Headquarters.” New York State. https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/17/details.aspxPerkins, Russell S. “Yorktown Campaign.” George’s Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/yorktown-campaign/“Preliminary Structural Assessment of Old Balmville School.” April 11, 2008. Roth, Eric. “Jonathan Hasbrouck Family Papers, 1751- 1904.” Historic Huguenot Street, October 16, 1999. https://www.huguenotstreet.org/jonathan-hasbrouck-family-papers/Ruttenber, Edward Manning. History of Orange County, New York. Philadelphia: Everts and Peck. 1881. https://archive.org/details/cu31924028832693/page/776------. History of the Town of Newburgh. Newburgh: E.M. Ruttenber and Company. 1859. https://archive.org/details/historytownnewb00ticegoog/page/n10Sparks, Jared. The Life of George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the American Armies, and First President of the United States: to Which are Added His Diaries and Speeches; and Various Miscellaneous Papers Relating to his Habits and Opinions. London: Henry Colburn Publisher. Vol. 1, 1839. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106019735858;view=1up;seq=11Van Kleek, Robert Boyd. Memorial of Thomas Powell, Esq.: Who Died at His Residence in Newburgh, on Monday, May 12,1856, in the Eighty-eighth Year of His Age. New York: Private Circulation. 1857. https://archive.org/details/memorialthomasp00kleegoog/page/n12Vaux, Calvert. Villas and Cottage. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1874. https://archive.org/details/villascottages00vaux/page/n9Visit Orange County. “Fun Facts.” Orange Tourism. https://orangetourism.org/fun-orange-county-facts/“Warren Delano, Resident of China.” Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Family History in the Hudson Valley. https://omeka.hrvh.org/exhibits/show/fdr-family-history/warren-delanoWashington, George. “Newburgh Address: George Washington’s to Officers of the Army.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/education/primary-sources-2/article/newburgh-address-george-washington-to-officers-of-the-army-march-15-1783/Woods, Lynn. “Lost Newburgh: The Tragedy on Urban Renewal: Part 1.” Newburgh Restoration. January 17, 2018. http://newburghrestoration.com/blog/2018/01/17/lost-newburgh-the-tragedy-of-urban-renewal-part-1a/------. “Lost Newburgh: The Tragedy of Urban Renewal: Part 2.” Newburgh Restoration. January 18, 2018. http://newburghrestoration.com/blog/2018/01/18/lost-newburgh-the-tragedy-of-urban-renewal-part-2/------. “Lost Newburgh: The Tragedy of Urban Renewal: Part 3.” Newburgh Restoration. January 19, 2018. http://newburghrestoration.com/blog/2018/01/19/lost-newburgh-the-tragedy-of-urban-renewal-part-3/

Replies to this post

|